Oct. - Dec. 2024

Paris, France

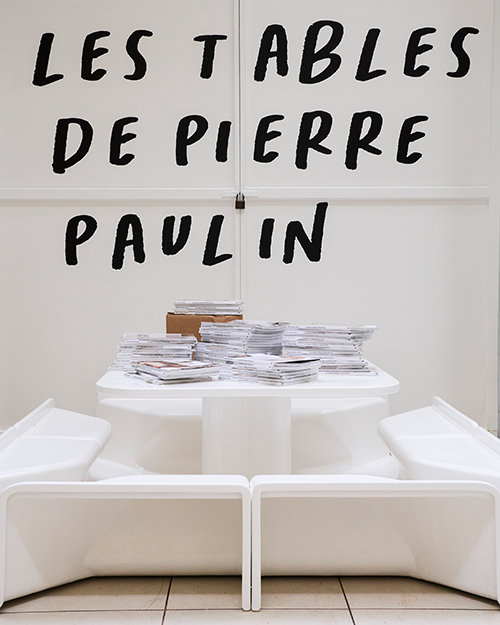

Les tables de Pierre Paulin

Pierre Paulin, the designer of modernity and French elegance who knew the vocabulary of style, flatly asserted that he loathed all that was hard. In this case, he was talking about the walls and partitions of dwellings and reception spaces.

His most famous seats (the Oyster, the Tongue, the Tulip), as well as the salons of the Élysée palace and the other places he worked on, are often structured as very soft textile cells. He took a keen interest in rugs as ‘places of life’ and very succ...

Read more

Discover our news